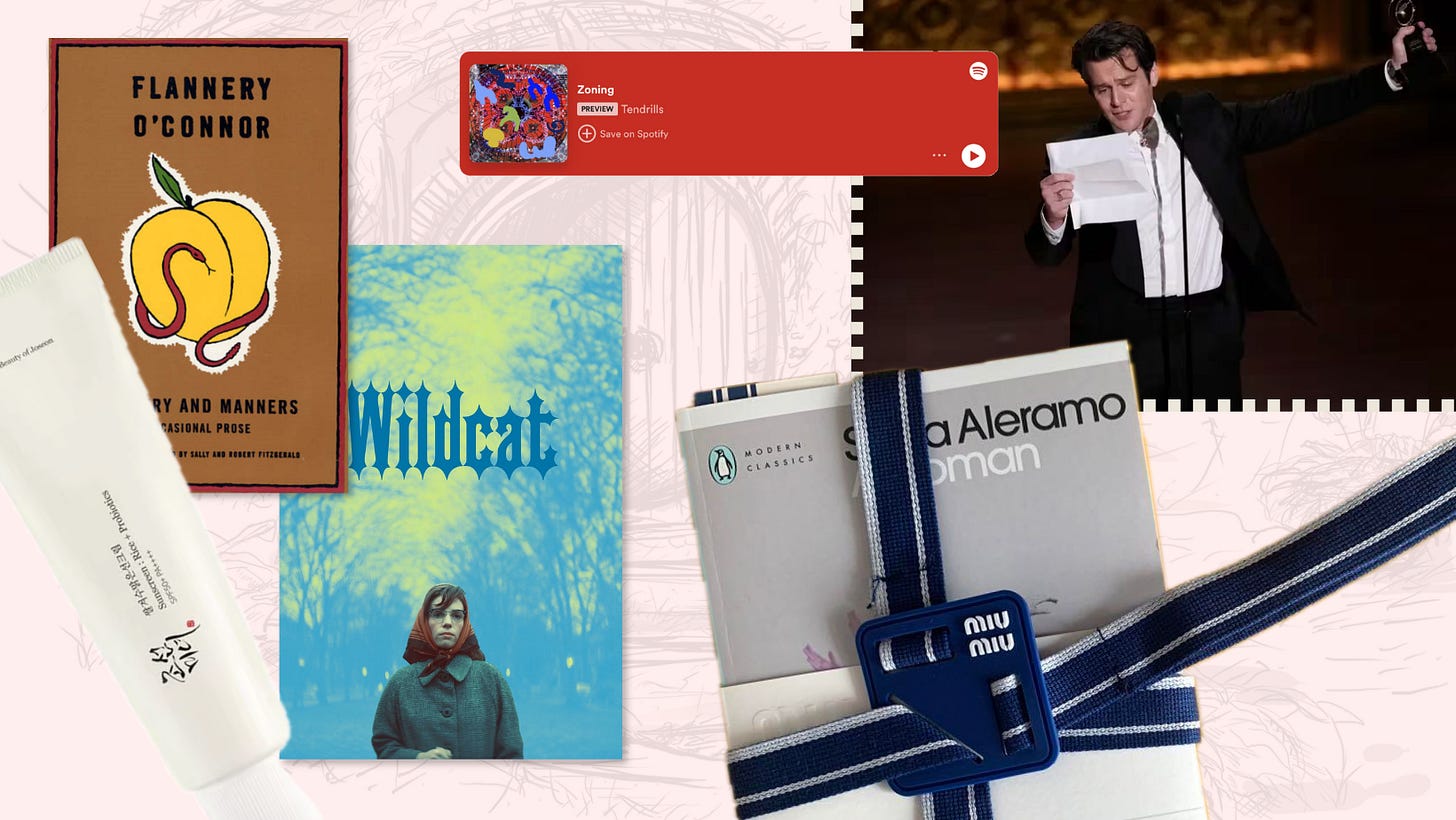

I saw the Flannery O’Connor biopic Wildcat last week. The movie covers a short period of Flannery’s life (a trip back home to Georgia while in the middle of novel revisions that turned into a permanent move thanks to her lupus diagnosis) cut with dramatizations of several of her short stories, including “Revelations” and “Good Country People.” I enjoyed it— several scenes made me laugh, especially when she says in a letter that she’s working on short stories because her novel is stupid and she didn’t want to look at it anymore (me)— but think the movie could have been more successful overall; the more biographical sections seemed a little confused and apologetic, blurred with content from her fiction for no reason I could clearly see, and so I imagine it would be even less coherent for people unfamiliar with the broad strokes of O’Connor’s career. The story dramatizations, however, really shone, giving the viewer the opportunity to experience her work and brilliance directly instead of through second-hand allusions (always a tricky part of art about artists, especially cross-mediums, in my experience).

O’Connor is a writer I admire more than enjoy: her depictions of humans and humanity are keen and clear-eyed to what I find an almost unbearable degree, like a too-well-lit dressing room whose lucidity of vision is oppressive. O’Connor’s writing is inseparable from her Catholicism1, which is perhaps part of why I struggle with it, but her clarity of purpose when it comes to writing, reading, and fiction is so compelling and inspiring. After seeing the movie I went back to Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, a collection released posthumously of some of her writing and lectures about writing, Southern writing, Catholicism, and Catholic art (and one essay about peacocks). Like her fiction, her nonfiction is sharp and perceptive and suffers no fools2. It’s fascinating craft writing, even as a non-Southern and non-Catholic, and without speaking overmuch about her own work does give a remarkable insight into what she was trying to do, what she values in fiction, and why she thinks fiction is important.

In the essay “The Fiction Writer & His Country,” O’Connor discusses the Southern Grotesque from the point of view of a Christian writer:

The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience… you have to make your vision apparent by shock— to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures. (33-34, emphasis mine)3

To O’Connor, nothing is so essential in fiction as portraying truth accurately, concretely, specifically, and dramatically. Most importantly, this should all be done (and done well; she has no patience for writing that uplifts the pious at the expense of good writing4) in service of her “Christian concerns;” that is, her concern with the Catholic mystery of the universe and of the miracle of grace. Few to none of her characters are explicitly Catholic (correct me if I’m wrong but I also reread her Collected Stories this week). She is far more interested in observing the world she lives in with its insufficiencies and foibles intact.

That belief is the whole point of it, and the thing that affects its form, style, and characters. Her characters are grotesque not just because she particularly enjoys depicting the ugly or the violent or the stupid, but because she feels an imperative to observe the world carefully and communicate her observations acutely and with such vividness and interest to hopefully communicate that worldview to the reader. Here it is maybe worth noting that O’Connor’s opinion of her contemporary readers is not particularly loving, an opinion I am maybe not cynical enough to 100% endorse but….. understand. She recounts an “old lady” who writes her a letter saying “that when the tired reader comes home at night, he wishes to read something that will lift up his heart… One old lady who wants her heart lifted up wouldn’t be so bad, but you multiply her two hundred and fifty thousand times and what you get is a book club.”5

In the lecture “Novelist and Believer,” O’Connor elaborates:

The novelist doesn’t write to express himself, he doesn’t write simply to render a vision he believes true; rather he renders his vision so that it can be transferred, as nearly whole as possible, to his reader… Distortion in this case is an instrument; exaggeration has a purpose, and the whole structure of the story or novel has been made what it is because of belief. This is not the kind of distortion that destroys; it is the kind that reveals, or should reveal. (162, emphasis mine)6

The real grotesque in O’Connor’s fiction are the hypocrites, the simperers, the idiots, the Pharisees, the holier-than-thou. Her work is violent, she acknowledges, but generally that is because violence is the most expedient way to get her characters to do what she needs them to do: break down, surrender (or fail to surrender), and reveal the truth (whether than be of themselves, of the world, or the world beyond). Her lectures make explicit that sociology does not interest her (in fiction): psychology does not interest her (in fiction): social justice REALLY does not interest her in fiction. Only the theological and the materials it takes to convey that view are important.

The real grotesque in O’Connor’s fiction are the hypocrites, the simperers, the willful idiots, the Pharisees, the holier-than-thou.

I spent plenty of hours of my childhood killing time in church libraries and Christian bookstores. The names and authors are indistinct blobs in my memory, various teen paperback series about Christian dating and saving first kisses and standing up to friends who think church is lame all blur together. Suffice to say that, like O’Connor, I hold no love for religious fiction as such. I have no wish to ponder the questions of Catholic mysticism; last week, without having thought too much about it, I would have said I abhorred any work of fiction that sought to teach me a moral, particularly a Christian one. And yet despite all that there’s something that appeals to me about O’Connor’s spiritual orientation to literature that I can’t quite put my finger on, but I think it’s that I do after all admire fiction with a conviction, one that makes both choices and judgements.

Of course judgement, as a function of belief, is essential to O’Connor. In the “Novelist and Believer” lecture, she explains that “showing feeling” is not the job of the fiction writer:

Great fiction involves the whole range of human judgement; it is not simply an imitation of feeling. The good novelist not only finds a symbol for feeling, he finds a symbol and a way of lodging it which tells the intelligent reader whether this feeling is adequate or inadequate, whether it is moral or immoral, whether it is good or evil. And his theology, even in its most remote reaches, will have a direct bearing on this. (156)7

Compared to the Tao L*n alt-lit offshoots whose work I’ve encountered with more frequency over the last year, I suspect what I’m reacting to is the depth of feeling that comes with reading fiction that is willing to convey judgement (and is built to do so through careful observation and concrete, true-to-life writing), that has a moral take (and one that it takes somewhat matter-of-factly true, rather than trying to evangelize you to its point). I don’t think there’s much more I can take of the disaffected post-post-internet lit that iterates a day’s events like a grocery list with a careful lack of emotional distinction between, say, opiate use and buying a new skirt. It’s not that there’s no place for that kind of work, but it at best leaves me feeling as depressed as its narrator and at worst leaves me with nothing, having dissipated in the time it takes me to order another glass of wine at the reading or turn the page. Maybe all this is my anti-irony pro-earnestness argument all over again.

O’Connor castigates her poor audience in “Writing Short Stories” for confusing stories with “a sketch with an essay woven through it” or “a reminiscence” or “opinion” or “anything under the sun but a story.” A story, she explains “is a complete dramatic action— and in good stories, the characters are shown through the action and the action is controlled through the characters, and the result of this is meaning that derives from the whole presented experience.8” Fiction requires change; from the Christian perspective, what better or more natural change than conversion, but the lesson applies more broadly, I think.

I take this lesson to heart: I have been banging my head against a handful of short stories lately. They’re technically fine; they have a beginning and an end but ultimately go nowhere (or, if they do exhibit change, don’t have enough scaffolding for it throughout the story). In my case, I think my problem is with characterization; I haven’t spent enough time building the characters (in my head if not on the page), and therefore they aren’t coming across as real enough to me or a reader. Maybe what they need is a little more judgement, too.

Anyways, that’s what I’ve been thinking about this week. If you made it this far, I thank you. Here’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.”

With love,

Courtney

What I’ve been reading/watching/consuming this week:

Maybe niche content but I love it: The Moral Economy of the Shire, by Nathan Goldwag.

Article in Vogue Business by Madeline Schulz on fashion brands and the trendiness of literature/books/etc. I generally am very interested in this (I admit I do kind of want one of those Miu Miu book straps! embarrassing) but I wish (and am hopeful) that we see a bit more money flow towards lit, particularly living writers (certainly Miuccia could have ‘hand-selected’ one living female writer of the three who could have used the sales, eh?) and supporting existing lit communities and indie bookshops in addition to stylish installations. (Not either, just and.) What if Prada supported a lit journal? What if Kaia Gerber threw a month’s private jet allowance toward reviving Astra? What if The Row bought a page at the back of the Sewanee Review? As important as it is to divorce art from capitalism I think we all know that arts funding, like a good man9, is hard to find. I think there are fun opportunities here and I would love to see some actually interesting work in this space. (I will consult for clothing tbh!)

An interesting review of Anne Carson’s body of work by Emily Wilson in The Nation.

Earlier this week, river otters were spotted outside the Baltimore Aquarium, on an almost-complete floating wetland area that’s been under construction for a few months. If you don’t know this about me yet, please understand that otters are one of my favorite animals and if I have the chance to catch even a glimpse of them happy and relaxed in my city (practically my neighborhood even!!!!) I will lose my mind in the best possible way. Also great news for the environment &etc but mainly good news for ME.

Grace Robbins-Somerville, for Paste: “Are we entering the golden age of baby fever anthems?”

In other music writing news: Tendrills’s new single “Zoning” got a mini review in Obscure Sound this week.

Hometown boy Jonathan Groff won his first Tony award this week. His acceptance speech, which begins with “growing up surrounded by cornfields in Lancaster County Pennsylvania,” choked me up a bit. 🥲 10

A great article from Julia Carpenter in Esquire on reading and censorship in prison. “One of the people on the other side of the request form—the one pulling books from the stacks to be sent to solitary—had an agenda of their own. When Harris requested books about abolitionism, activism, and other issues, she instead received religious titles from Christian and evangelical authors.”

Beauty of Joseon’s summer sale is on til 6/30; I am (mostly by ginger necessity) pretty obsessive about sunscreen and theirs (and everything else I’ve tried from there) is a very good & unobtrusive everyday one.

She was also arguably racist, a question I don’t find very compelling in this context, but worth acknowledging.

In the lecture “Writing Short Stories,” which was composed by the editors from a talk she was invited to give at an undated Southern Writers Conference, she roasts the hell out of the attendee manuscripts she was submitted and among other remarks says “My calm was shattered when I was sent seven of your manuscripts to read. After this experience, I found myself ready to admit, if not that the short story is one of the most difficult literary forms, at least that it is more difficult for some than for others.” To their faces!!

In the lecture “Novelist and Believer,” she writes, “Ever since there have been such things as novels, the world has been flooded with bad fiction for which the religious impulse has been responsible.” 🔥 Mystery and Manners, p 163.

Ibid, p 48.

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid, p 89-90.

Flannery joke :)

In fairness it takes so little for a decent acceptance speech (in the arts) to make my cry but this one especially!

"I spent plenty of hours of my childhood killing time in church libraries and Christian bookstores. The names and authors are indistinct blobs in my memory, various teen paperback series about Christian dating and saving first kisses and standing up to friends who think church is lame all blur together."

YES. I could smell one of the Christian bookstores I frequented in middle school when reading this.

I thought of you when Jonathan mentioned Lancaster County! Have you seen the video of the first performance post-Tonys and the applause that interrupted the show?