Making Conversation

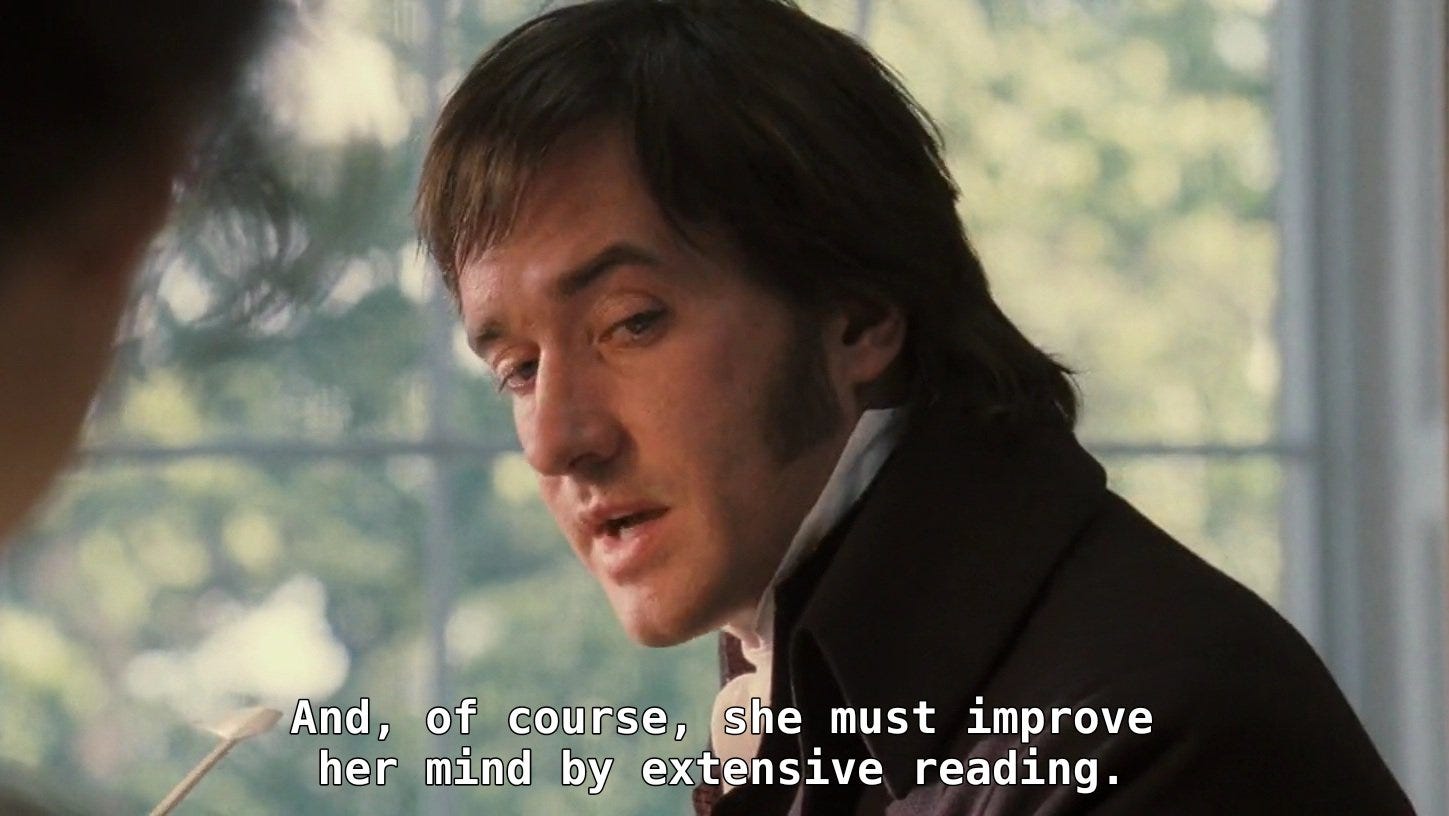

On Jane Austen & leaving things unsaid

Good morning.

This newsletter has existed for a few months, which means I’m overdue to write about Jane Austen.

I don’t remember reading Pride and Prejudice for the first time. I assume it happened during my early homeschooling days, around twelve or thirteen, when I was making m…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Country of the Story to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.